System Zero and Shadow System

This article was originally written in French in 2013 and revised in 2018. It has been translated in English by John Mettraux and is available both on his website and on lapinmarteau.com.

The Shadow System

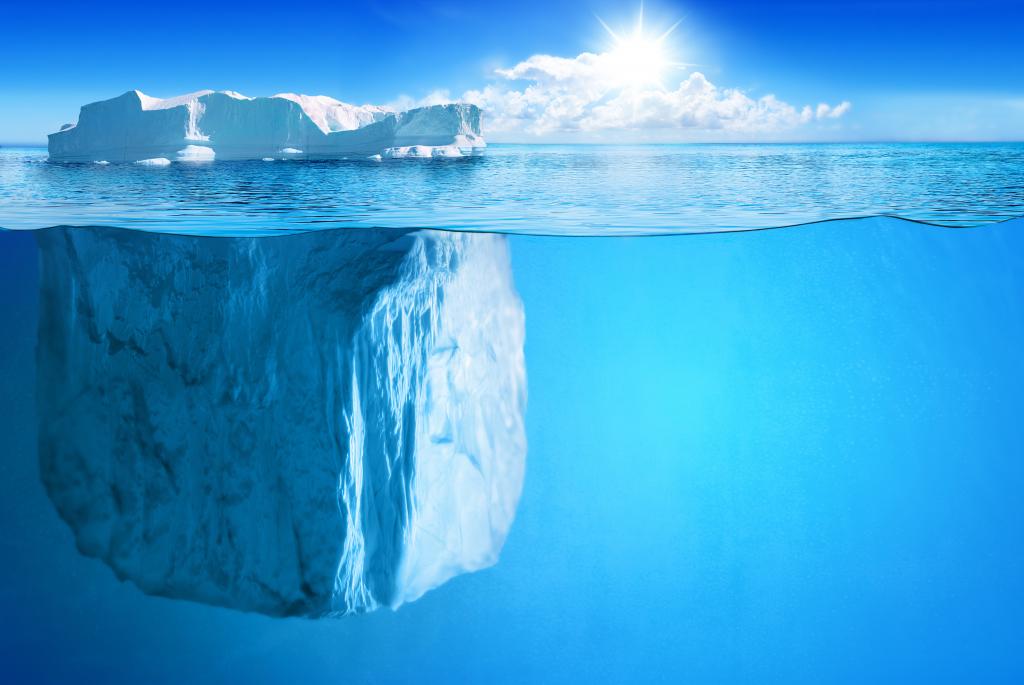

How does a gamemaster handle an in-game situation for which they see no solution in the rulebook? They fend for themselves. Or, in other words, they fall back to a default system that may be dictated partly by circumstances, by the conventions of their group, by what they think is the essence of TTRPG, or by something else, and they apply that system to solve the issue. The reason for which they see no solution doesn’t matter in itself. It might be due to the game, its completeness or incompleteness, the practices of the group, the way they made the game their own, etc. What matters is that there is, akin to the submerged part of an iceberg, a way of playing specific to the group and it completes and substitutes itself partially to the way of playing proposed by the game, even for those groups that try to play by the book.

Most of the time, the gamemaster is not aware that they are using an alternative system, as their rules are tied to their own way of playing, even to what they consider as TTRPG or the fundamentals of TTRPG. Thus, one may regularly find the following rules: « The most realistic option is chosen », « When in doubt, favour the player characters », or « In case of dispute, both roll a dice and the highest wins ».

In the first version of this article, this alternative system, often implicit, was defined as the System Zero of the gamemaster, the group, or of the session. In practice, the use of this term was mistaken for the concept presented below and it became necessary to use another concept. As ideas were exchanged during a conference abroad, a term came to the fore: Shadow System. It thus encompasses the rules used in the interstices of the game system, sometimes instead of it, and that Shadow System notably states when the game system should be followed or not. For example, if a gamemaster refuses to kill player characters in their sessions, the rules of the game do not matter, they’ll be bypassed to apply the implicit rule « one does not kill player characters ».

This shadow system is pretty much the difference between the game as it is played and the way it is written (erratas and explicit houserules included).

The System Zero

If one moves from scale of a single group to the scale of multiple groups, might it be possible to define a kind of common Shadow System, a default system for a majority of people, of which other TTRPGs would in fact be variants or some extensions? A kind of lowest common denominator, a minimum playable version of the TTRPG. It might even be a way of defining it.

Clearly, that definition would highlight a single type, a « form », of TTRPG among others, and multiple variants of that form might exist. But this hypothetical system would be what is called « System Zero ». Very roughly, it would probably look like:

Setup

– Someone decides about the universe/setting of reference, the characters, and the initial situation.

– Anything not specified happens either a) as it would in the reference setting, or in the « real » world if no reference setting was chosen or if this setting does not cover that point, or b) it will be discovered during the session as needed.

Possible Moves

– When a player wants their character to perform some action, they tell it to the person holding the authority at that point (usually it’s the gamemaster, but that may vary) and that person decides, on their own, of the validity, the success, and the consequences of that move.

– If the gamemaster wants something to happen that is not a consequence of a player decision, that does happen.

End of Session / End of Game

– The session ends when the players all agree that it should stop, or when they cannot agree that it should continue.

Victory Conditions

– The player characters survive, in other words, the may be played again in a potential next session.

– Achievement of any fictional or internal game objective specified earlier in the session.

On top of that, there is the particularly common convention that wants the gamemaster to factor in a combination of the three following criteria when taking their decision: internal coherence of the universe, relevance — or formulation — of what the player says, and the supposed capabilities of the characters. Once again, there exist a certain number of variations, but they do not change that core. That a decision was taken by the gamemaster, another player, or the group, or that the decision was inspired by a dice roll or not (as long as the dice roll is not requested by a procedure of the game one is currently supposed to play), these decision mode do not change the core above, the System Zero.

In short, one reaches a rules system that is often referred to by some French-speaking players as « sans dés » (diceless), « sans règles » (without rules), « full karma » and some other names. It is important to understand that this is a complete system, not just a resolution mechanism. To focus only on the latest would roughly correspond to what is generally called « roleplay » by French-speaking players or to letting the gamemaster decide (they both mean almost the same thing here). But what counts in the matter, well beyond the mechanics used, is that there is a common base vaguely compatible between all the TTRPG players, with the probable exception of complete and unguided beginners, or less mainstream « forms » of TTRPGs. A way of playing such a system would roughly be considered as « by default », or « as in any other TTRPG ».

A small parenthesis to stress that if those two points do apply on rules in their classical sense, they equally apply to the universe, and for all other subsystems1 that a TTRPG might encompass. The universe/setting being just one of those subsystems, traditionally delivered in a slightly particular format.

So what?

Clearly, this talk of « Shadow System » and « System Zero » is an artifice (almost a « legal fiction » for the latter), and it is not, especially as presented in this post, very robust from a theorical point of view. For the « Shadow System », one can even talk about a gamemaster/group « style », and it’s probably even better, because more directly graspable (even if, by going from « Shadow System » to « Style », two or tree things get lost if one wants to go further, and among those things, the formal side and the link between the two meanings). It’s not that serious. In fact, as much as each gamemaster/group having their « Shadow System » does matter, as much as knowing if a « System Zero » in its second meaning exists or not does not matter. It’s foremost a useful notion when debating certain points at the creation of a game.

1. In order to be used on top of the table, each game element must earn its place, whatever that place is, and convince of its usefulness. Game elements are in concurrence with elements in the « Shadow System » of the gamemaster/group, even if those elements are of the « rule of thumb » kind.

2. A game will only be complete and played as the authors intended it with the juxtaposition of what is in the rulebook and of something else. No exceptions, this applies to all the games, even your favourite game2.

3. Hence, there is no issue with a game requiring a common base or some given know-how (once again, all the games do), but those prerequisites, even when unexplained, should be clearly identifiable for the reader, even before acquisition, especially if the reader doesn’t know that common base, those know-hows. They should at least be enumerated.

4. In the same way, one almost always play with two systems, specificities coming from the game one has acquired, that plug themselves on the local « Shadow System ». Most of the gamemastering techniques actually consist, beyond plugging holes, in not using the rules as written.

And most importantly, always with the aim of evaluating one’s own rules:

0. Any rule placed in a system must deal with its object better than if it were dealt by simply roleplaying it (for instance) by players trusting each others. One must know in what way it is better or else get rid of the rule. Motivations behind the rule like, it belongs to the genre (mental health in horror games, localisation in tactical games, etc), all the other games have it, or « else it would lack that rule », are not sufficient. Filter all the rules through this sieve and a lot of useless complexity will be gone without giving up anything that makes the richness of the game.

In other words, whatever the rule one wants to add to a game, the first question to ask is « Does it make the game more interesting than if simply using the System Zero instead? ». The second question is « Then how so? ». To answer, a clear vision of what one wants to obtain (a criterion) is necessary. If the answer to one of the questions is not satisfying, the rule under scrutiny more than likely needs to be ridden of.

Notes

1(this list is appears in a smaller post about sous-systèmes)

What types of subsystems can be found in a TTRPG?

– group or setting creation/setup at beginning of session/campaign

– character creation

– creation of new rules, powers, or other « hard » content

– guidelines about the possible gamemaster moves (if there is a gamemaster)

– endgame

– impact of a character on the next character of the same player

– scenario / session / personal arcs / campaign generation

– management of the roles/tasks of players inside the group (different of those of the player characters)

– « macro » management of the opposition

– safety tools (x-card, lines and veils, etc)

– rewards (and potentially approval or sanctions)

– distribution of speech and authority

– resolution / simulation

– ad-hoc subsystem to focus on particular « in-game » points (mass combat, combat, damage, mental health, management, duel of wits, magic, travels, etc)

– structure and/or rhythm of a session

– …

Even if the limit is fuzzy, I am voluntarily excluding any rule going outside of the context of the game to determine if players are behaving poorly (are boors). Some of these terms may not be very clear. Sorry about that, in the worst case I’ll write a further post about these subsystems.

2 (This is a smaller post about niveaux de règles)

Here is another quick post in the series about the rule notion. This time, it focuses on the different levels of rules used in our beloved games and, as an example, what makes for a surprising reveal when game authors are spectators to sessions of the games they crafted. Far from rocket science, just a few quick definitions that may prove useful when creating a game or when debriefing a playtest.

The three main rule levels:

– RAI (rules as intended)

– RAW (rules as written)

– RIP (rules in play), rules as they were used in session, in other words as they were interpreted and eventually completed

RIP are composed of:

– RAIn (rules as interpreted)

– HR (house rules), formalization of additions and customization

– IR (informal rules)

A transposition to soccer:

– RAI: the players shouldn’t behave dangerously

– RAW: a red card is issued as a sanction for certain behaviours

– RIP: as a player, if what you want to prevent (taking a goal, lose the title, …) is more penalizing that being kicked out with a red card, it’s more rewarding to behave dangerously

A few quick points:

– RAI never exactly map to RIP in TTRPGs.

– It’s not severe, it’s not an issue, it’s not even a sign that the game is bad. As long as the RAW do hold up.

– One of the goals of the authors should nevertheless be to ensure the RAW are as close as possible to the RAI, and also as close as possible to RAIn, unless there is a specific and thought through desire not to precise certain elements in order to obtain a certain effect.

– A player sometimes thinks about getting the RIP or the RAI, but they are reading the RAW and they shouldn’t have to worry much for RAI once they have the RAW at hand.

– The only level of rule that can be referred to in a clear manner are the RAW. There might be some rare exceptions with groups that took the time to formalize their playing habits.

– That may sound idiotic, but it applies only when rules are actually written. It is not the case with all games.

– Rules that are written and are part of the game but are not formal may exist. That’s the case for all the rules brought by the setting or the visuals of the game.

That said, more advanced classifications do exist. David Parlett distinguishes:

– Foundational Rules are roughly the foundations, especially mathematics, on which the game is based. It could even mean things as trivial as how to read a dice or what to do when it’s chipped. Those rules are generally implicit.

– Behavioral Rules concern ways of playing with others without becoming a pain in their ass, for example « thou shalt not play games on your smartphone during a TTRPG session ». They are generally implicit. Often, when one talks of unwritten rules, these are what is referred to.

– Operational Rules are specific to the game, explain how to win, allowed and forbidden moves, eventual interactions with the material, etc. It’s often what is referred to when one says « the rules ».

– Written Rules, the written and formalized version of the Operational Rules, or nearly so.

– Laws, roughly a written and formalized version of Behavorial Rules, generally coming with a list of sanctions. Indispensible for gaming in group.

– Official Rules, the way the game is played in official competitions. They comprise Written Rules, Laws, and for example some conventions and errata.

– Advisory Rules (strategic rules), mostly pieces of advice on how to better play.

– Feedback Rules, that map somehow with houserules as described above.

As always, those terms and definitions are only valuable if they are used for some purpose. Simply asking oneself the question, when creating a game, of what are the rules that one thinks may be fundamental or not (in a TTRPG for example, having a gamemaster may not be fundamental), and thus one might play, enhance, modify, is already a very useful exercise. Same thing, maybe even more, for Behavior Rules (interactions between players, note taking, etc).

Aucun Commentaire